By Daniel Tarade

Note: Stories of suicide can be difficult to read. If you're dealing with mental-health concerns, help is available. If you're in crisis or in need of assistance, call 416-408-HELP, go to your nearest hospital or call 911.

An increasing number of people are dying from suicide each year. A recent US report by the CDC highlights that, of the 50 states, half experienced increases in the rate of suicide by 50% or more from 1999 to 2016. Only one state experiencing a decrease. I recently argued the benefit of subway barriers as a strategy for reducing suicide. I attempted to dispel with the notion that by preventing people from dying from suicide in our subway system, they would simply die from suicide somewhere else. It remained an abstract concept, though I indeed cited a paper reviewing suicide trends that made such a claim. I was curious to see hard data, not only to assuage my own doubts, but to convince others that we cannot remain idle when it comes to suicide prevention. There are strategies that can work! Today, we will discuss such data. Today, I advocate for us to be compassionate towards those who have died from suicide and those who are at risk.

Hvistendahl, M. (2013). In rural Asia, locking up poisons to prevent suicides.

It was only a few weeks after writing about suicide in Toronto that I stumbled across an article published in 2013 about suicide in south-east Asia.[i] Rather than worry about subway barriers, the major concern in south-east Asia, particularly the rural farming communities, is the ingestion of herbicides and pesticides. In certain regions, swallowing these deadly poisons was the number one reason for hospitalization. The high suicide rate in this region of the world has resulted in pesticides being used in one-third of the roughly one million suicides that occur annually around the globe. Although the method of suicide may vary, striking similarities between suicide in North America and south-east Asia are apparent. In both, suicide is often not associated with any discernible mental health crisis, precipitating instead from impulsive decisions made during a period of acute emotional distress. According to the recent report by the CDC, half of all people dying from suicide did not have a known mental health condition. It would follow that having access to the implements of suicide alone would raise suicide rates as no one is immune to emotional distress. The smoking gun.

Kreitman, N. (1976). The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-71. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 30(2), 86-93.

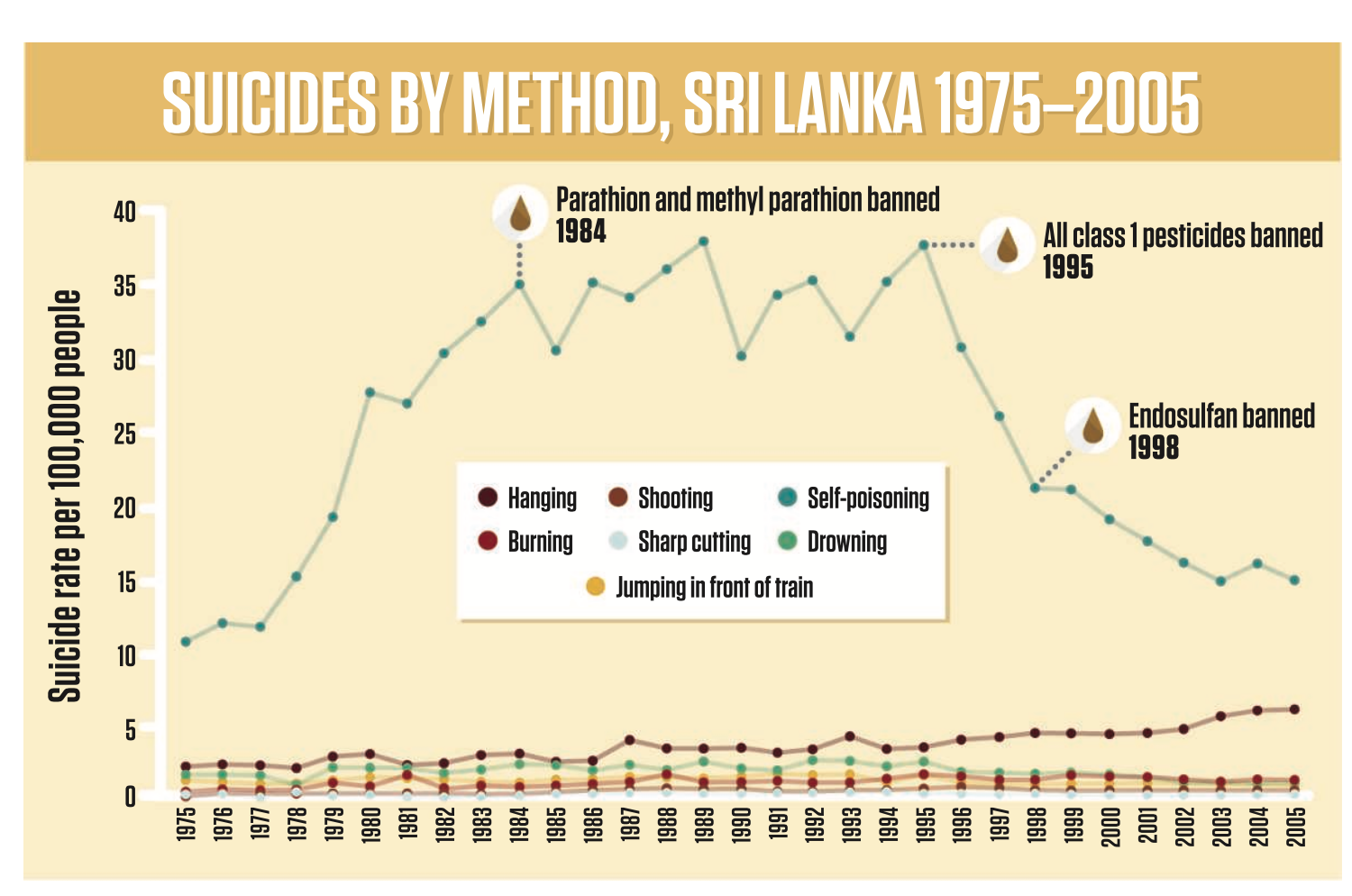

As incredibly toxic pesticides and herbicides became common on rural Sri Lankan farms during the green revolution in the 1970s, rates of suicide via self-poisoning increased from 10 per 100, 000 to 35 per 100, 000 with suicide rates via other methods remaining unchanged.[i] As these very same pesticides were banned, the rate returned to near baseline levels, again without a concomitant increase in rates of suicide via other methods. Access to a means of suicide is associated with suicide. The same trend appears in other parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, as gas stoves were eliminated from households, suicide via carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning was almost eliminated.[ii] Although the rates of suicide via other methods increased in some demographic groups, generally they remained stable.[ii] The exact same trend was noticed in Switzerland when domestic gas was detoxified; the result was an overall decrease in suicide.[iii] In America, having access to a gun is correlated with suicide.[iv, v] In Asia, villages with a greater proportion of tall buildings have higher rates of people jumping to their death.[vi] You get the idea. When trends are dissected like this, it seems so simple. Yet, the ramifications are clear and ought to be acted upon; restricting access to the means of suicide can reduce suicide rates.

It is tempting to assume that people who die from suicide are a lost cause. That they refused to help themselves. If this were the case, we could justify our collective inaction; an acceptance of periodic tragedies. But when people sit down and talk with survivors of suicide attempts, a different picture emerges. Roughly half of all suicides are deemed to be impulsive, with little planning or forethought.[vii] How impulsive is impulsive? Half of people who survived a suicide attempt reported that the duration between their first thought about suicide and their attempt was less than ten minutes.[viii] A death in the family, legal or financial troubles, or relationship difficulties can bring about an acute struggle that, if lethal means are in proximity, can be enough to bring about demise. I can understand why this is a difficult concept to accept; nobody wants to think that they could ever find themselves in a similar position where death seems to be the best outcome. However, if we collectively do find peace with the fragility of human life and its many intricacies, we can begin to construct societies that mitigate that risk for all people.

The increasing rates of suicide are a complicated problem, much like homelessness and addiction. When problems are spiralling out of control a tempting strategy is to blame the victim. As the homeless are lazy and the addicted are fiends, those who die from suicide are hopeless. The first step then becomes to stop moralizing the very people who are suffering most. If we do accept that the people who are in desperate situations are not different than we are, at least not in any meaningful sense, we can make collective sacrifices for the betterment of these people. Stem the tide! For those who die from suicide, this would involve raising awareness of the signs of an impending suicide attempt, increasing funds for crisis resources (helplines, emergency care), and decreasing access to the means of suicide. However, I do not want to paint a picture that the changes needed to be made are completely known and trivial to implement. Barriers exist. For example, an attempt to mitigate suicide via poisoning in Sri Lanka by locking up agricultural pesticides failed to reduce suicide rates, suggesting that complete removal of toxic pesticides may be necessary.[ix] In countries like the United States, the right to bear arms renders any limitations on access to guns politically improbable. But it is worth the effort to make an effort. It is known that the majority of people who survive a suicide attempt do not go on to die from suicide.[v] Lives can be saved, families can be spared. But first we need to intervene.

But, intervention is only the beginning. The underlying problems also need to be resolved. From the dramatic decrease in Sri Lankan suicides brought about by banning incredibly toxic pesticides, one might be mistaken into thinking that the problem has been largely addressed. The rate of pesticide ingestion, however, remains unchanged.[i] It is just that people are no longer dying as the available means are less lethal. It is a strong start that buys time. For the same reason, people have advocated that prescription opiates may help stem the fentanyl crisis in North America. Recognizing that expecting individuals to simply quit highly addictive drugs is unrealistic, tantamount to a death sentence, safe injection sites and prescription opiates (that are less likely to cause an overdose) follow logically. When you stop moralizing the victims of the capitalist-pharmaceutical complex, it becomes untenable to simply watch people die. Yet, once people stop dying, the need for healing begins. Steps need to be taken to provide therapy.

All action must begin with compassion. I advocate for a restriction on the implements of suicide because I believe these deaths can be prevented. Yet, impeding on a person’s freedoms without rectifying the conditions that have made suicide commonplace in society is an empty gesture. More so when one considers that suicide is not universally bad but depends on the particulars. I personally endorse doctor-assisted suicide as an option for person’s suffering with poor health or unmanageable pain. Suicide that arises from mental illness that is not being treated can be addressed by greatly improving upon mental health care systems. Suicide that arises from tenuous financial situations, seen among Indian farmers,[x] can only be addressed through changes in our economic structure. Societies need to be terraformed for the betterment of people. We need equity for all on economic, social, and political fronts. But, this all starts with compassion for those who are most vulnerable.

[i] Hvistendahl, Mara. (2013). In rural Asia, locking up poisons to prevent suicides, Science, 341(6147), 738-739.

[ii] Kreitman, N. (1976). The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-71. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 30(2), 86-93.

[iii] Lester, D. (1990). The effect of the detoxification of domestic gas in Switzerland on the suicide rate. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 82(5), 383-384.

[iv] Wintemute, G. J., Parham, C. A., Beaumont, J. J., Wright, M., & Drake, C. (1999). Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. New England Journal of Medicine, 341(21), 1583-1589.

[v] Miller, M., & Hemenway, D. (2008). Guns and suicide in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(10), 989-991.

[vi] Lin, J. J., & Lu, T. H. (2006). Association between the accessibility to lethal methods and method-specific suicide rates: An ecological study in Taiwan. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

[vii] Baca-Garcia, E., Diaz-Sastre, C., Basurte, E., Prieto, R., Ceverino, A., Saiz-Ruiz, J., & de Leon, J. (2001). A prospective study of the paradoxical relationship between impulsivity and lethality of suicide attempts. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

[viii] Deisenhammer, E. A., Strauss, R., Kemmler, G., Hinterhuber, H., & Weiss, E. M. (2009). The duration of the suicidal process: how much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt?. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

[ix] Pearson, M., Metcalfe, C., Jayamanne, S., Gunnell, D., Weerasinghe, M., Pieris, R., ... & Bandara, P. (2017). Effectiveness of household lockable pesticide storage to reduce pesticide self-poisoning in rural Asia: a community-based, cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 390(10105), 1863-1872.

[x] Kennedy, J., & King, L. (2014). The political economy of farmers’ suicides in India: indebted cash-crop farmers with marginal landholdings explain state-level variation in suicide rates. Globalization and health, 10(1), 16.